Unironically Loving the New Flesh

When mechs appear in fiction they direct the flow of time; the world enters a “mecha age.” Every world development and every actionable expression of power is performed through mecha conduits. This mech-as-singularity is partly to make the fiction interesting, partly to sell shit. But, I wouldn’t call it groundless. Post-war irony is the beating heart of the “real robot” genre. If both sides have mechs, then what was the point of mechs? Except, that is, mutually assured destruction.

This projected future of robotics is quietly developing to be unreal. The dark pulsing goal of Boston Dynamics is to create an inexhaustible workforce. When one “professional” is in charge of ten robots, capitalists can fire ten workers. In contrast, a giant robot requires a network of dozens of workers to protect, create, and utilize one asset (at this point if giant robots ever exist it will be because of mechafic, not in spite of it). Maybe that’s why mechs are nearly always imagined in military contexts. They are, essentially, anthropomorphized tanks. Strategic deployment of something deadly, expensive, and difficult to use, has a chance of returning that level of investment, supposedly. Unless the opposition has mechs too (they always do).

Still, the unreality and excess of mecha is a focal point, creating boundaries to explore futures that can’t and shouldn’t happen. Futures that resemble scars past. Yet, I feel these stories are often compromised by unflinching myths. A soldier’s self-critique is realistically limited by a war happening at all; if the commonality between these stories is war, then war becomes the point. There’s a thread of Mark Fisher-like “realism” in that mechs are almost always imagined to go to war and are almost always imagined in the realm of assets and investments. It’s easy to think, what else would an anthropomorphized tank be for? Despite that, for me, the war ambience is usually the least compelling part of mechafic.

Mechafic’s singularity-like “war realism” resembles real attitudes in the technology sector. Making things to help and improve each other’s lives should be a direct kind of good, right? Robotics could have all kinds of uses that I feel less inclined to list, because my point is, the only imagined application for invention is in the realm of assets and investment. Venture capital “innovation” scams are basically treated as the height of contribution to our civilization. Of course that’s bullshit, but when you witness the presence of people like Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, Elizabeth Holmes— the venture capital messiahs—it’s impossible not to notice the lethal amount of Randian energies they give off. They act like “chosen ones.”

Whether by magic, birth, or natural talent, mecha-fic is permeated by special wunderkinds, and the direct parallels between sci-fi pulp and real life tech attitudes would be funny if it wasn’t too real. Special wunderkinds is a trope that is patterned in fiction from these capitalistic attitudes, the cold logic that if someone is better, smarter, or faster, they’re worth more. I bring this up because teenage me would fantasize about being a mech pilot. Even after watching the horrors and stress of the position ruin the characters again and again, the consequences of “being good at something” and being good at something seemed separate. Because mechs are so unreal I could think, if they were real, and have some distant teenage hope.

There’s a fine line between expressing the horrors of war and reveling in violent exceptionalism. Even mecha-fic that tries its best gets it wrong sometimes and that’s because war is fucked. I think it’s okay to express that, but the thing is, videogames have almost always gotten this horribly wrong. I’ve played an embarrassing number of mecha games. The goal is to get better at destroying things to make more money. Little room for nuance. Just a wrong that’s leveling, deep and flat.

Because of its divergence in priorities, the mecha videogame can be thought of as a separate off-shoot of mecha fiction, as it totally embodies a corporate ethic. Either you head a mercenary venture (MechWarrior) or you’re a contractor looking for thrills and riches (Armored Core). The core of either is a libertarian venture that would make BioShock blush. A throwaway line in MechAssault tells the player character to stomp on infantry in order to save ammo. You know, casual war crimes. The mercenary group is solidly portrayed as Halo or Mass Effect-type heroes—it’s not like they were making subversive “bad guy” games on the Xbox or anything! I mean, what the fuck!

Even a release as recent as Brigador, despite its attempts at being subversive, puts the player-mech-pilot in a familiar role: a contractor for a shadowy corp causing massive destruction for $$$. “Disruption” comes to mind. The active logic of wunderkinds piloting technological singularities meets the passive logic of game design and becomes deadened. Like, this is what people thought and still think videogames are for. The mecha videogame reflects the market realism of the videogame industry; lone geniuses wrangle down military-grade technology in order to make big cash, collateral damage be damned.

Acknowledging this I still appreciate mechs on a granular level. Mecha-fic and even mecha games have characters coming to terms with a transformation of their body—exhibiting these bodies in new and different contexts that are often terrifying and exhilarating. Part of the fantasy is that, well, it’s something I’m bad at; whether putting myself out there, or making changes to myself, in any context. But the other half is fixation on learning that is almost kind: the focus on learning how to pilot, on the mech’s necessary maintenance, and on the mechanical body’s limitations. This focus, even in oblique metaphor, can make care feel nearer and attainable. If I can learn to love a weird metal body I can learn to love a weird one made of meat.

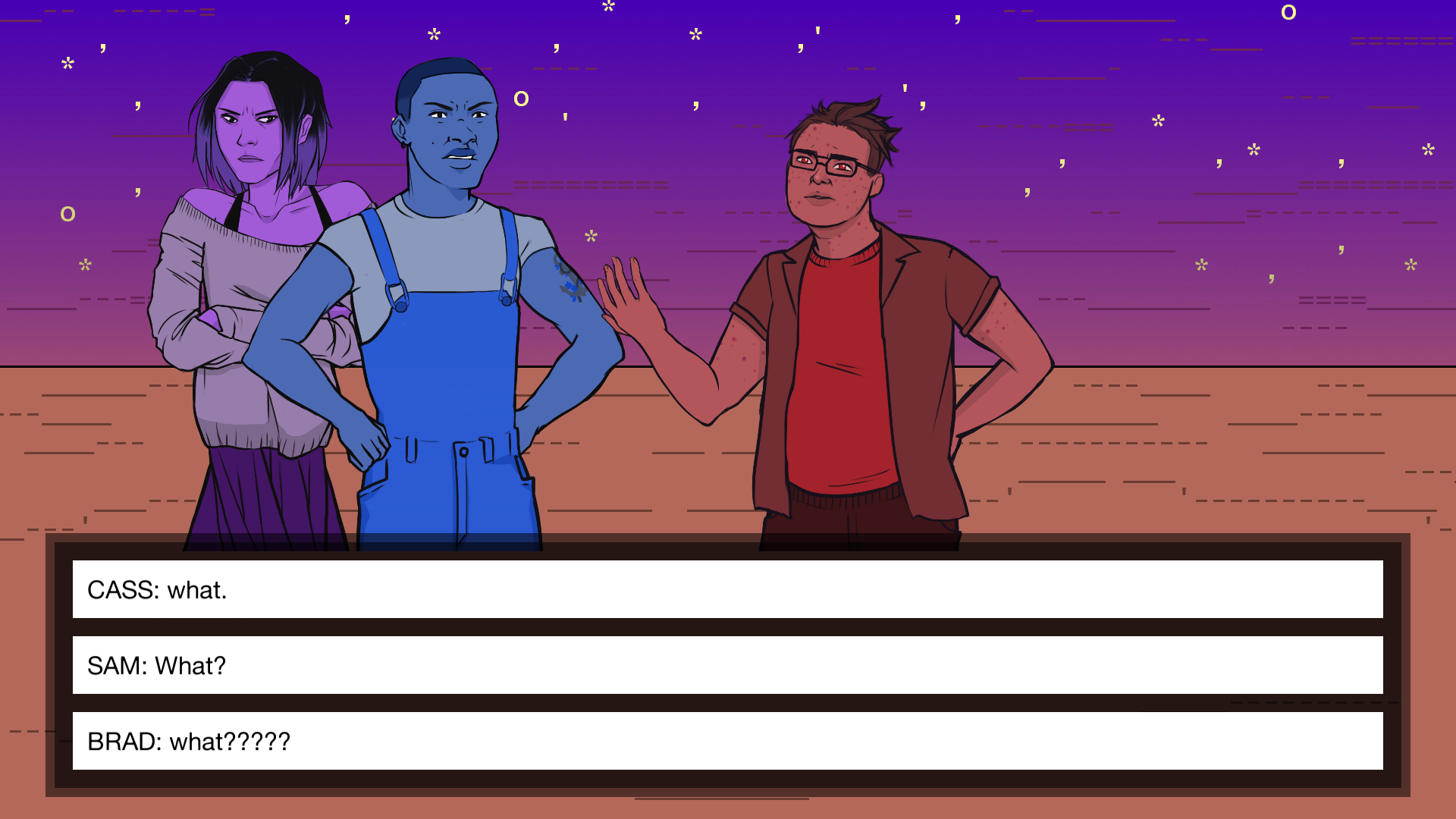

I love Extreme Meatpunks Forever because it’s holistically about loving your own self and body; being able to accept the space it takes up while fighting any bastard bigot that says otherwise. Mechafic curses are consciously avoided: no one in the cast is a special genius, no one is trying to make a quick buck, and none are commandeered into being tools of the state. It might be redundant to state as much, but consciously refusing those tropes gave me a lot of hope.

The fact that the mechs are bodies (they’re made of meat, so like, meatpunks!) makes emotional subtext behind mech piloting, well, explicit text. Dialogue in pre-fight monologues and post-fight dream sequences emphasize that the mechs are different, or adjacent, or extended bodies, rather than just being better. More than that, these moments focus on the double-edged nature of violence. Meatpunks posits violence as definitely necessary, while maintaining distant respect toward the consequences. Never is the choice made lightly. These displays of honesty and vulnerability are straightforward, stunning, and welcome. A heavy contrast within the sea of games that are scared to interrogate or consider their violence at all.

>Fighting is presented in a way that exemplifies brutal necessity—the best fights in the game narrativize mech fighting as the only way out of being cornered. The straightforward shapes that build and flow through the mech fighting amplify the singular aesthetic; only that which is necessary is present because violence is something that is done as necessary. It’s stark and complimentary. (Unfortunately there is a big chunk of somewhat random, filler-tier battles that balk on this promise. When the punks are being chased, the fighting is justified, but it starts to feel samey and excessive, and so to some extent, contradictorily unnecessary).

Though, despite my own fixation on the subject, the game is a bit sparse with the nerdy mecha worldbuilding I crave. Mechs in Meatpunks take a backseat to its focus on character interactions and interpersonal relationships. It’s infinitely refreshing to play a game with characters that legitimately sound like myself and people I know. Because the writing resembles, I don’t know what to call it, internet speak? It’s more “realistic” and “contemporary” than faux-objective-realistic screenwriting that gets billed as those things. Still, Meatpunks’ clarity toward the subject helped me frame a lot of arguments and figure out uncomfortable suppositions toward mecha-as-symbol. Thus, I feel the critiques I outlined throughout help to appreciate Meatpunks.

But I do want to say that stumbling through, and winning, the final fight with Cass is the most hopeful catharsis I’ve felt with a videogame since, well, it’s been a long time (for once I don’t feel like spoiling what happens in my review). Partly responsible for the catharsis is everything good about the mech combat I’ve outlined, but the other part is genuine relation. Relating to them and feeling like someone gets it. It means a lot to me to see non-binary representation that isn’t overwhelmingly bad or overwhelmingly good. It’s not just a story about pain or reflecting on it; the ending captures the struggle that fostering hope requires. This is the kind of thing I knew was possible but kind of gave up hope on seeing in games. Meatpunks inspired that hope back in me. I want to steal the goddamn sun too.

published 9/7/2019